| |

-

The will to subvert gains control of the record making machinery

2 May 2000

-

|

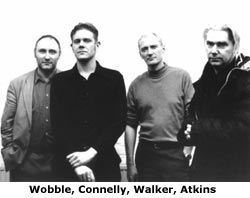

A couple of decades ago drummer Martin Atkins and bassist Jah Wobble built the musical framework for what was arguably the punk revolution’s most cogent and incendiary statement: the band Public Image Limited. But contexts change and what is most dangerous in 2000 is not what made people shit themselves in 1979. Hence, The Damage Manual.

In Atkins’ words, the band’s mission is to “insert little bits of gelignite for later use in people’s brains... and to just walk away smiling knowing that one day, you know, there’s going to be a bunch of little explosions in somebody’s head.” In other words, The Damage Manual’s aim is no less than to subvert the world via catchy (if creepy) music, one brain at a time.

Atkins—whose drumming helped define Nine Inch Nails, Ministry, Pigface, and many other breakthrough acts—now heads Chicago-based Invisible Records which publishes CDs by the likes of Psychic TV’s Genesis P. Orridge, Killing Joke, Murder Inc., Sheep On Drugs, and Test Dept. He continues to work with a who’s who of noise and punk, as does Wobble—who himself heads up 30 Hz Records out of England.

Fleshing out The Damage Manual mercenary unit: Chris Connelly, the insidious voice of Ministry and The Revolting Cocks. And Geordie Walker, guitarist and musical visionary for Killing Joke.

The Damage Manual have just released their debut EP in both the US and the UK—it’s titled simply “1”. As the band prepared for their first ever tour, Rockbites caught up with Chris and Martin. Here’s the first installment of our conversation.

-

Rockbites: How would you describe the new EP?

Martin Atkins: It’s honest and it’s intimate so, you know, you’re kind of inside our brains. This band isn’t formulaic, it isn’t part of a major label, it’s not worried. It is what it is, and I’m not saying 'I don’t fucking care if not one person in California gets it.' Of course I care... because it’s a part of me, it’s a part of Wobble, it’s a part of all of us. But having said that, it’s not an integral part of any of us doing this to have it be validated by the approval of the mass market.

To me, the fact that we’ve had this experience and the fact that this record exists means we have succeeded, and if nobody gets it, well, fine.

Rockbites: On a much smaller scale, I hold the same attitude with Rockbites... I’ve got a vision of what I want to do. Within the limits of my resources I work toward that, and I hope that there are a few people out there who appreciate it. But I’m not trying for the lowest common denominator.

Martin Atkins: No, and it doesn’t make sense to do that. Because once you start to worry about anybody, you’re fucked. Because if you’re going to worry about one person, then does everybody in the band get to worry about one person? Then suddenly there’s like the equivalent of 12 people in the band. I think that there needs to be a direction, a unified thought process, even if it’s the product of four or five or six different people’s opinions. It needs to be magnified and focused and clear to communicate it.

Rockbites: Is there any sort of issue or work to do in terms of striking a balance between democracy and clear leadership in The Damage Manual?

Martin Atkins: Well, I think the band is in the process of becoming a band, and we’re all finding out what that means—in and out of the studio. And it’s actually pretty cool. I’m not used to waiting for anybody’s opinion before carrying on. I have a label [Invisible Records], we put out 160 CDs. I live in the studio.

I think initially it was difficult—well, initially, there wasn’t much input from anybody. I had some loops and ideas and we went into the studio and did our thing. And then I was left to take the ideas where I thought they should go. But I wanted this to become a band, and everybody else wanted this to become a band, so I think we’re all making... sacrifices isn’t the right word... but we’re all making... allowances, if you like?

Here’s why 'sacrifices' is the wrong word: Everybody is releasing their tight grip... slightly... and what do I get from doing that? Well! I get fucking Geordie Walker, and his opinion! And I get Jah Wobble and his opinion, and Chris Connelly and his opinion.

I’ve seen a lot of people in this business fail miserably because they surround themselves with sycophants and yes men, and that’s not the path to greatness. I think that whatever time-consuming difficulties are being thrown up by the fact that this is a band, I think that the end result is worth ten times that.

Rockbites: Who came up with the name The Damage Manual?

Chris Connelly: I came up with the name DAMAGE MANUAL—it was actually a song title. Now it’s called Damage Addict.

“There’s no artistry involved whatsoever when it is done correctly.”

Rockbites: Did you also pen the lyrics on the EP?

Chris Connelly: Yeah, I wrote all the lyrics on 1, as I did on the album. It was a real pleasure and a challenge!

Rockbites: The lyrics on 1 strike me as opaque, dark, and dreamy. They’re also spooky and evocative. Can you talk about the lyrical approach?

Chris Connelly: I suppose I approached the lyrics in the same way as I approach all my lyric writing, the major difference being that this time the music was already written. And that was good because it meant that much of the aesthetic suggestion was already there and my mind was reacting to something that was someone else’s catalyst.

Lyrically, I approached from the same dark place I always come from. Not because I am a dark person, it’s just that there is a certain part of my mind that I can only access through lyric writing. It is not a place I necessarily like, but I feel compelled to explore it because I think that it might unlock something in someone else. However, there is I feel a lot of humor embedded in these words. It’s my humor, so I guess you have to know me...

Rockbites: Can you reveal any of the song titles on the forthcoming album?

Chris Connelly: Age Of Urges, King Mob, Denial, Blistering Poles, Expand, Stateless, Peepshow Ghosts, Broadcasting... There are more, but I forget right now...

Rockbites: Martin, I read in your bio that you started a construction company after you left PiL. That kind of struck me out of left field. Would you want to say anything about that?

Martin Atkins: It seems very simple to me—although I’m going to dart backwards and forwards now and I apologize.

I have worked on music and come to a point where I say like 'this song isn’t powerful enough. Let’s bring in two more guitarists... OK, now let’s have the guitars go chung-chung-chung... OK, now we need another track of like violins! going eh-eh-eh-eh... No, it’s still not powerful enough...'

You go down these roads, and you keep going down these roads, and then you take the time to sit there... and as boring as it is, you just start listening to the drums, with the bass... like 'Oh... it’s not really quite jelling...' So you deal with those problems because in the low end, in rhythms, if things aren’t locked then they can cancel each other out. It’s very strange.

I did a thing called Murder Inc. with Paul Ferguson playing drums and I was also playing drums. And I told Steve Albini—I wasn’t producing, Albini was—I said 'Look, you’re not going to be able to like feature both drum kits at the same time. I know I’m paying for all this, but please just choose one drum kit and maybe have the other kit, you know, noodling around with it as a texture. You don’t have to feature both Paul and I, and I’m happy to tell you you can submerge my drums to be more of an effect, if you like.'

“So there’s obviously a parallel between music production and drywall construction”

If you’ve got two bass drums, it’s not as powerful as one bass drum. Sometimes it’s half as powerful as one because the beats, if they’re just slightly off, cancel each other out. When they’re extremly close together but not right on top of each other you get phase cancellation and they literally disappear.

And so I’ve worked on songs that I didn’t think were powerful, and I’ve immediately assumed that it was all of the embroidery instruments, if you like, in the upper range. And then I’ve ended up going back to the rhythm section and lining up the drums, and making sure the drums and the bass rock. And then I found myself starting to remove all of the reinforcing elements I’d put on the song to help with its momentum. Because for every reinforcement you put on there, you might gain a little bit but you also lose some of the nuances.

So there’s obviously a parallel with that and drywall construction, for instance. I mean, if you frame out a wall badly, without paying attention to the wall being level, or without measuring the wall, then when you take your 4' x 8' sheet rock or drywall... you know, maybe you’re working on your own, you push this sheet of drywall up against the wall and you go to put a screw in, and there’s no fucking wood there! right where you want the screw to go, because you just fucking didn’t pay attention. So then you have to kind of—while you’re holding the sheet rock—you’re pissed off ’cause you’re working with the sheet rock now, you don’t want to be working with 2 x 4s, but you cut up a couple of pieces and it’s shit, and it’s not quite level, so you got a bunch of screws going in, they miss the wood, and the two sheets that line up aren’t quite even, and you just think, well 'Fuck It!' So you end up, instead of just... I don’t know if you know anything about dry wall?

Rockbites: No, but I’m following you.

Martin Atkins: Well, there’s two big sheets, and you usually can’t see the seams when people do a professional job. And it’s not artistry. There’s no artistry involved whatsoever when it is done correctly. Because there’s like a trench on the edge of each piece, so when the two pieces line up all the screws go in the trench, and you put the tape down there, and you get a big blade, and you fill this trench with plaster—and that’s it! But if you do it poorly you end up having to become an artist, trying to camouflage these great big screw holes all over the place, and the fact that the wall is bowed... So you end up replastering a whole wall and it takes you five times as long, and the end result is shit.

So one lesson from construction is laying a solid, square, lined-up foundation. And you only have to do that once in construction and once in music to understand the parallels. And there are times when I’m in the studio and you could say I’m an artist—I’m running ten different effects units and tape delays and digital delays—and I’m on another planet! There are other times when I have literally got my sleeves rolled up and I am doing drudgery work, chopping out shit moments of a vocal or coughs or splutters or... you know, it’s shit work.

But it’s the only way to have any magic. And I know that that’s the way so I don’t mind doing it.

“If you’re going from zero to nasty, you can only go to 100% nasty.”

I built my own studio here. It’s inside a brick building but I’ve put another layer of brick in, I’ve bricked up some windows, put some glass block in, blah, blah, blah... I mean, I’m actually enjoying brick laying! In music—any kind of inspired, dangerous music—there are no tools to measure it. It’s just vibe and opinion. It’s great to work on a record for a year and then go and build a wall in the garden. And it’s like, 'OK, is that wall level? Well, let me put my spirit level on top of it and measure it and, yes, it is level. Does this wall exist? Yes it does, because I just fucking bashed my leg on it, and I’m bleeding. The wall exists!'

I’m sure some people would say, 'Talking about lofty ambitions, the ethereal, mystical nature of great music—what the fuck is he on about talking about concrete and plaster?' But I really like the two things together. Sometimes I’ll just be getting really pissed off in the studio and it’s great to work on something outside of the studio. It’s therapy for me, and I think the two things work very well together.

Rockbites: I see no contradiction. I’ve heard of, well of course, working from both sides of your brain would be one way to look at what you’re talking about, and another way is that I’ve heard some spiritual teachers talk about the 'spirituality of the mundane'—of just getting on with your daily chores, and how that can be a spiritual exercise as well.

Martin Atkins: Ah... well there you go then.

Rockbites: Yeah. OK, well that was very enlightening! So, that might answer another question I had, which was: when you started the construction company, were you turning away from music? Sounds like the answer would be no.

Martin Atkins: No, the answer was yes. See, at this point in my life I can be working on a mix, and I’m happy to take a full day or two day break from it to work on some construction while I think in a different way, or maybe I don’t even realize I’m thinking about a mix but of course I am. But in the early stages of this, I think the first time I got involved in construction was a definite one year long turning of the back on the music business. Absolutely. And that was because of personality shit. A level of disgust. And I was tired.

And I think that now I’m at a point where I can work on music for a day and go and work on some construction for a day.

Rockbites: Keeping things balanced.

Martin Atkins: Yeah. But early on it definitely felt like it was either one or the other. And it was only after a little while that I saw how the two could be kind of harmonious. If that makes sense.

Rockbites: It does—one of the advantages of living and getting older, and experiencing things.

Martin Atkins: Yeah. And I’d like to find something else, that isn’t construction and isn’t music, that takes me somewhere else. I mean I’d have to say my kids do that! You know...

“There are journalists and there are people within the industry who go 'Oh fuck, they’re back! Those fuckers!'”

Rockbites: So you have some kids?

Martin Atkins: I have a two year old and a four year old boy. And that has been a tremendously fueling experience. A lot of people have said to me 'Well, there’s the end of your creativity.' But actually it was the end of my time-wasting. It made my time feel more important. I felt like I had less time to waste, if you like. So I think it re-focused some things for me.

Rockbites: That’s very fortunate. Chris, do you have any kids?

Chris Connelly: I have no children, though I would like to one day. But I’m too selfish—in a good way!—to let anything detract from my creative process. The cats are enough right now. I suppose from my point of view, everything I am involved with on a collaborative level helps enhance some aspect of my personality. I take it all very seriously and I am concerned with what I can bring to the table, and how I relate to the others involved. Having said that, The Bells (which is really my solo project) is my baby, and I hope it reflects that.

Rockbites: Could you talk about the children laughing on the track Damage Addict? Somehow they make it extra threatening.

Martin Atkins: If I feel something I try to evoke a mood, and I just felt that kind of playground vibe. Sometimes I’ll just do that stuff for myself and it won’t be on the finished track... and that stuff is. I like the mood. I could see Geordie playing that guitar down at a river bank, just this quiet thing. And then Chris is doing that strange, almost creepy voice. And I just heard children laughing. And I think that a lot of what I’m doing is an experiment in 'How can I make this more, how can I make it sweeter? How can I make this particular moment harder, nastier, crunchier?'

I find myself turning to different textures. The way I like to make a moment nastier is by having it be surrounded by or followed by or preceded by a really nice moment.

It’s easy to make something really nasty! But how do you take that to another level of nastiness? Well, I try creating moments around that as sweet as I can, to create a massive difference in textures. If you’re going from zero to nasty, you can only go to 100% nasty. But if you’re going from 100% sweet to 100% nasty, you’ve got a 200% shift in mood.

Rockbites: Ah... well put.

Martin Atkins: That’s where I’m experimenting at the moment, and I’m having a pretty good time.

Rockbites: I’ve heard actors say similar things. Kevin Spacey was talking about his death scene in LA Confidential. He said the most effective possible approach, when he got shot, would be to exhibit almost no reaction whatsoever—to just kind of fade away. And I just heard an interview with Anthony Hopkins. He was saying he reckoned the most terrifying experience for Clarise, the FBI agent, upon meeting Lector would be for him to be just standing in the middle of his jail cell, smiling.

Martin Atkins: Yeah! Oh, I mean, if you want to—I know this because I’ve done it—if you’ve got ten people, ten nasty fuckers coming at you and you just start laughing... that’s the most dangerous, frightening thing you can do! But if you go 'Ohhhh come on then! I’m going to fucking kill you fuckers!' ...it’s just expected. Oh, yes, a bit of danger. But you start laughing! Going 'Here, alright! Hah, hah! Ohhh, this is going to be a hoot!' Then immediately five of the ten people go 'Oh shit!'.

And I think that’s what The Damage Manual is. I think we’re all just gleeful at the idea that—without setting out to do this... we just get together and do our thing—I think the end result is a bunch of people standing around going 'Oh shit!'

I’m sure, you know, Geordie would say there are journalists and there are people within the industry who go 'Oh fuck, they’re back! Those fuckers!' Because I don’t think that we conform to any ideas. We’re not controllable in the sense that a major label can say 'Listen guys, would you wear these tartan trousers, and it will help you get to the goal you’ve told us you have of being on television.'

Our goals I think are much more internalized and much simpler. And our ideas of success are both deeper and simpler than a lot of people’s ideas of success. So, you know, I think there is a whole group of people who are just like 'Oh, fuck! They haven’t disappeared.' And, you know, it’s more dangerous than ever.

|

|